Software Sustainability in Computational Science and Engineering at PASC22

Back at the end of June this year (⏲ where does the time go ⏲), I attended quite a unique and interesting conference called The Platform for Advanced Scientific Computing (PASC) 2022. As the name suggests, it is a highly interdisciplinary conference that pulls together scientific domains with a high reliance on computing—from plasma physics and molecular simulations to economics and data science. In a future post, I am hoping to give a broader picture of some of the content I came across at the conference, but in this post I want to focus on a minisymposium session in which I was a presenter.

The title of the minisymposium was Software and Data Sustainability in Computational Science and Engineering 1. You can follow the link for the full description of what that means, but my personal distillation of the objective of this session was as follows:

In the context of the explosion of software in research and the complexity of the hardware and software environment upon which this relies, how do we ensure the sustainability of the software produced during research? In particular, what are the human factors that are a challenge for RSEs and RSEng?

This is a multi-faceted topic, and the strength of the symposium was that we each addressed this topic from quite a different level and scope. At the pan-institutional and international scale, there was Dr. Anna-Lena Lamprecht’s talk about policy and community in research software. One tier down from this was my talk looking at how a central RSE team can effectively promote software sustainability at an institution. And finally at the embedded RSE and individual level, there was Hannah Williams’ talk giving an insightful analysis of the trade-offs necessary between expediency and sustainability when operating under extreme time constraints. You can find and cite the presentations using our Figshare collection for the minisymposium.

I will now dive a bit deeper into each presentation and give my thoughts and impressions.

Good-Enough Practice – Reflections on a Pandemic Response

Hannah made a great statement at the start of her presentation: “no one sets out to do a ‘bad’ job”. If that’s so, then why does unsustainable research software exist? One reason is that as individuals and teams, we are constrained by situations and external forces that require trade-offs between good practice and delivery time. This probably better know in the software engineering world as the ETTO (efficiency-thoroughness-trade-off) principle.

We are all constantly making decisions about where our code will sit on the ETTO scale, and in Hannah’s case these decisions had to be made under incredible pressure. She is part of the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) and was involved in that department’s COVID-19 response. Government agencies and the public in general were dependent on the vitally important and timely information her team were producing with their analyses and codes. The main factors influencing Hannah’s team’s ETTO decisions were:

- time

- constantly evolving situations and requirements

- staffing and onboarding

- data access and quality

- inability to release source code because of privacy concerns and lack of priority compared to other objectives.

Those sound pretty familiar to me! Even so, one might think that because this case is a bit extreme, it might not offer any lessons for one’s own software development occurring in far less high-stakes settings. However, my view is the opposite. I think Hannah’s experience provides an insightful lens with which to focus on the absolutely essential good practices that simply cannot be abandoned in a project. According to Hannah, these are:

- Sense-checks and informal peer review when automated testing isn’t possible

- Openness about limitations of results and including disclaimers

- Modular code

- Automate processes where possible (i.e. CI/CD)

- Some documentation is better than none (even if it is just an email with some usage instructions)

- Software community and coding clubs.

I am in near total agreement with all of these “good-enough” practices as they are usually some of the first aspects I try to implement in my own projects (viz. modularity, CI, documentation, code review, testing). In my opinion, automated testing should almost never be abandoned, with an obvious exception being a case like Hannah’s where the re-use of certain codes can be quite low and program verification is a lower priority than model validation. Using model validation and “sanity checks” as a quality assurance technique has been the status quo across science for many years, and it has served us well, but it is important to recognise that it can be inefficient when it comes to teasing out errors in computer code. I have written about the importance of software testing previously, so I won’t go into any further detail here.

Overall, Hannah’s presentation outlined some essential practices that all of us as individual RSEs should reflect on and put into practice. There is also the hint of the need for collective action through communities that I will expand on in the next section.

From the Trenches of a Central RSE Team

As an individual RSE, there is only so much one can do to change the tide of software sustainability. In large institutions like universities or national laboratories, dedicated teams of RSEs that exist independent of any particular research group have started forming to provide the resources and skills needed to improve software sustainability. My talk addressed the strategies and operational model that my particular central RSE team at UKAEA (UK Atomic Energy Authority) uses to improve the development of research software.

First, some context for my team is necessary. Fusion science is a broad domain both in terms of areas of science and spatial and temporal time scales, leading to what I describe as a “heterogenous computing environment”. For instance, creating a high fidelity “digital twin” of a fusion reactor would require approximately 10 TB and 5 million CPUs, putting it firmly in the exascale of computing, and it requires simulations based on plasma physics, materials science, mechanical engineering, etc.

In addition, we face the problems of:

- legacy code

- lack of awareness and buy-in to good software engineering practice

- absence of unified software development policy

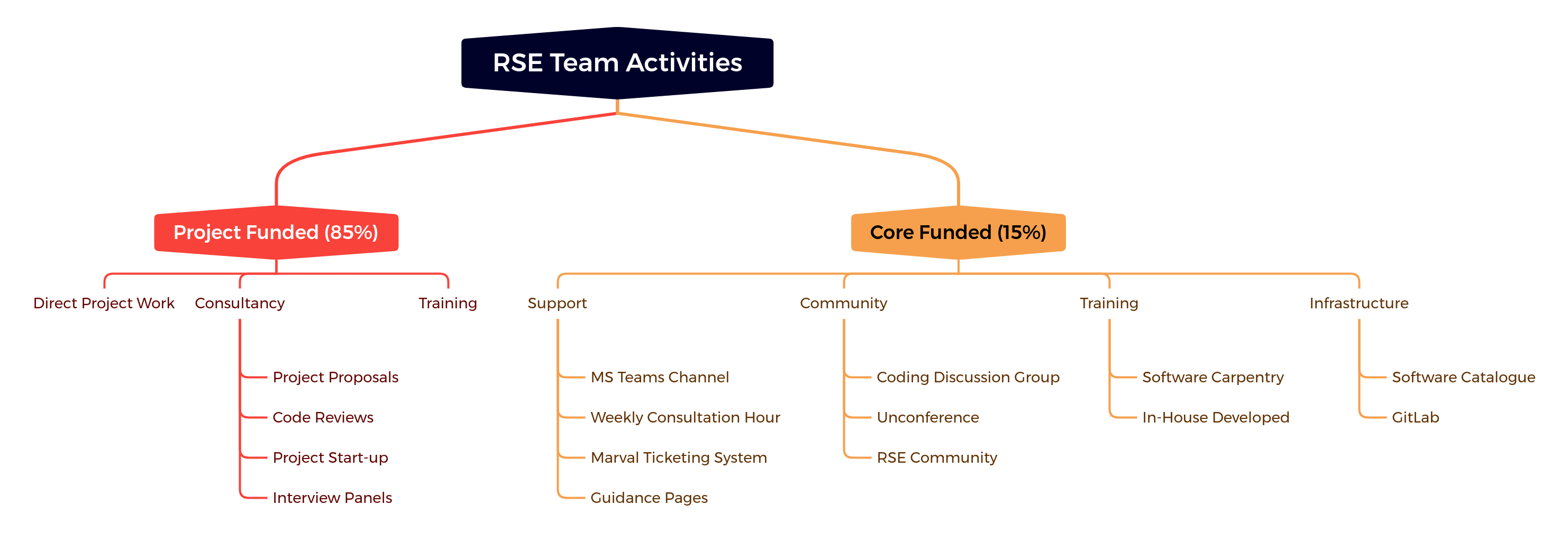

These are not unique to our institution, but it is worth sharing our strategy and activities for tackling them, which is summarised in the image below.

Bluteau, Matthew (2022): From the Trenches of a Central RSE Team: Successes and Challenges of Promoting Software Sustainability in a Multi-Scale Computational Setting. figshare. Presentation. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20473515.v1

Bluteau, Matthew (2022): From the Trenches of a Central RSE Team: Successes and Challenges of Promoting Software Sustainability in a Multi-Scale Computational Setting. figshare. Presentation. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20473515.v1

I suspect like most central RSE teams, our time is predominantly spent on work funded by the projects of other research groups. It is our bread-and-butter, and it is truly important work to do. One of the best ways of spreading software sustainability is practicing what you preach. There is an important subtopic of this work that I call “consultancy”, which deserves mention because it is one way that we can directly influence the structure and planning of research projects so that they consider software sustainability from the beginning rather than as an afterthought, at which point it is much more difficult to correct course. We have advised on project funding proposals in the past and sat on interview panels, both of which plant seeds for future software sustainability. We have also done one-off code reviews, usually on quite large portions of existing code bases with the purpose of getting them fit for release. Whilst we aim to encourage regular code review as part of merge requests in all substantial software projects, this doesn’t always happen, and it is still important to support the projects that haven’t adopted this practice yet. This is a subject close to my heart because it was one of the first “side” projects I got assigned when I initially started as an RSE and because I have been an active participant in the Research Code Review Community.

Although project-funded work takes up the bulk of our time, I place an equal importance on the smaller portion of our work that is enabled by some core funding (the right side of the figure above). Why? Because not being tied to any particular research project means that we can do work that we believe benefits all research groups on site, allowing us to start building a research software infrastructure and baseline that will hopefully make our project work easier over time. The activities under this core funding umbrella are quite varied, and I have been lucky enough to participate in most of them. For example, under the “Community” heading our team runs something called the Coding Discussion Group, which is a monthly meeting dedicated to research software topics. At the moment, this takes the format of a short presentation to inspire subsequent discussion, but in the future, I am hoping to make it more interactive with actual coding activities to facilitate learning through practice, similar to the “coding club” Hannah described in her talk. And as Hannah explained, fostering this software community is a foundational part of good software development because it enables knowledge and skill exchange.

I would be remiss not to also mention the “Training” subtopic. For over five years, our team has been delivering the regular Python-based Software Carpentry Workshop along with some of our own material on automated testing and best practices. Early this year, I lead a successful pilot of the new Carpentries course “Intermediate Research Software Development in Python” as the main thrust of my SSI fellowship, and it has now become part of our regular offering.

It is my hope that this brief summary of my groups activities will be helpful to other groups in their effort to promote software sustainability.

Improving Support and Recognition for Research Software Personnel - the International Landscape

Expanding further the scope of consideration, it is necessary to acknowledge that even central and embedded RSE teams cannot solve all of the problems of software sustainability because they operate in a global research culture that still does not adequately value research software as an output. This means these teams are constantly fighting an up-hill battle and unable to operate at their full potential. The international action and culture change needed to improve this situation is what Anna-Lena’s talk addressed.

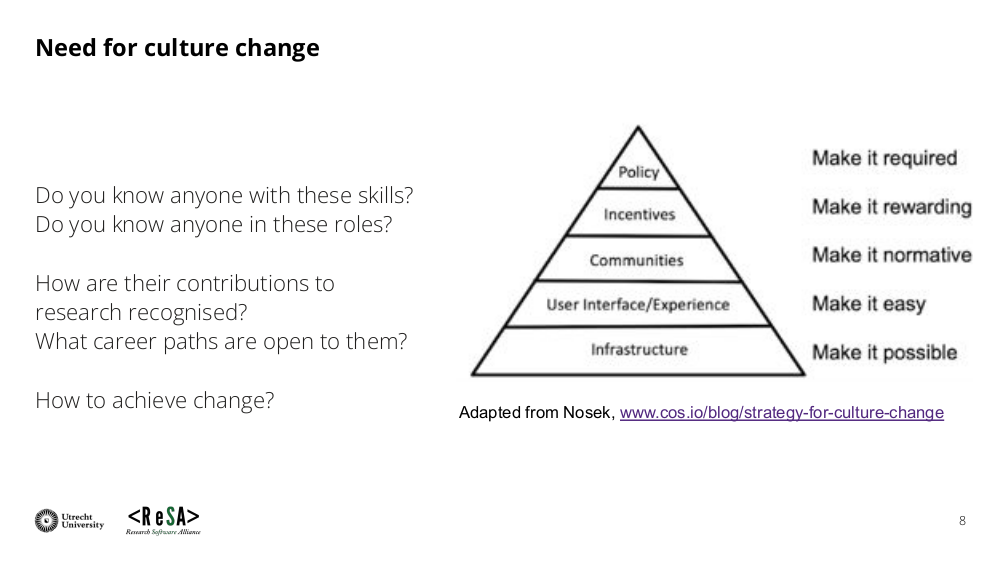

She succinctly gave the roadmap for culture change in the slide below:

Lamprecht, Anna-Lena; Barker, Michelle (2022): Improving Support and Recognition for Research Software Personnel - the International Landscape. figshare. Presentation. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20492739.v1

Lamprecht, Anna-Lena; Barker, Michelle (2022): Improving Support and Recognition for Research Software Personnel - the International Landscape. figshare. Presentation. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20492739.v1

What I particularly liked was her comment that this is meant to be simultaneously a bottom-up and top-down approach, something I have long believed in. At the bottom of the pyramid are the categories of infrastructure and skills (substitute for “User Interface / Experience” in the figure), which are slightly different from the infrastructure and training that were mentioned in my talk above, which was focussed on RSEs providing the services for researchers. Rather, the infrastructure and skills Anna-Lena is talking about are specifically to support RSEs. An example of infrastructure she gave was something like the Citation File Format (CFF) that easily facilitates the citation of a code repository, helping RSEs get cited and therefore closer to proper recognition. This is also something that was produced directly by a few RSEs. Bottom up approach FTW!

On the skills side, Anna-Lena identified a new group called INTERSECT that is looking at what skills RSEs specifically need to develop their career. Again, this is different from more general research software skills that both researchers and RSEs require, like the foundational common ground the Carpentries has built. I have not had much contact with this group yet, but I am very interested in getting involved. It strikes me as a nice mix of both bottom up and top down approaches. It is supported by the NSF (top-down) but was presumably first submitted by a group of researchers (bottom-up).

Next in the pyramid is communities, a theme that arose in all three presentations. This highlights that communities are needed at many different levels in order to support software sustainability. As RSEs, we are quite lucky that an extensive international network of national RSE societies has developed with the movement. Wherever you are in the world, there will be a society you can join as an RSE to get support and network with other RSEs. These national and international communities are essential because not every institutions or research area will have an appropriate community for an RSE to join.

Moving one more level up the pyramid, we come to incentives. I think incentives are closely linked with recognition, and this is confirmed by the fact that Anna-Lena mentioned things like the Hidden REF and progress in the Netherlands towards considering all outputs (including software) when making decisions about hiring and promotion. Ultimately, software sustainability depends in large part on RSEs being widespread in research, and that can only happen when they are properly recognised and rewarded for their contributions to research.

Finally, at the top of the pyramid for creating culture change is policy, which encapsulates most of the “top-down” aspects of this framework. It is the policies of funding bodies, universities, and publishers that create the environment in which research culture forms, meaning there is only so much that research culture can deviate from the limits enforced by this policy environment. Concerted advocacy and lobbying over many years will be needed, and Anna-Lena pointed out organisations doing this work like the Research Software Alliance (ReSA), Software Sustainability Institute (SSI), and the FORCE11 Software Citation Working Group. I would add that many national RSE societies are also engaged in policy advocacy, a specific example being the discussions that SocRSE have had with funding bodies in the UK.

-

Those paying attention will notice that data sustainability is in the title but not really mentioned elsewhere in the post. This is because the session itself really focussed on the software side of this problem. Historically, there has been much more done on the data side (e.g. FAIR principles) in research than the software side, so it feels natural there has been a shift. Obviously, the two are intertwined, and both require the success of the other to fully achieve their aims. ↩